David Dungay Jr, who died in the Long Bay jail in New South Wales in December 2015, and Shaun Coolwell, who died in Logan hospital after being arrested near Brisbane in October 2015, were both administered with midazolam.

An inquest into Coolwell’s death began this week and an inquest in Dungay’s death is expected in July.

They follow concerns about midazolam being used in other deaths in custody.

Dungay, a 26-year-old Dunghutti man, died in the mental health unit of the Long Bay jail in Sydney just three weeks before his expected release after he was injected with midazolam while being physically restrained.

Guardian Australia spoke to medical or legal experts and practitioners who said the use of the sedative is safe in controlled circumstances, but many warned its use during the physical restraint of a prisoner was dangerous and could be fatal.

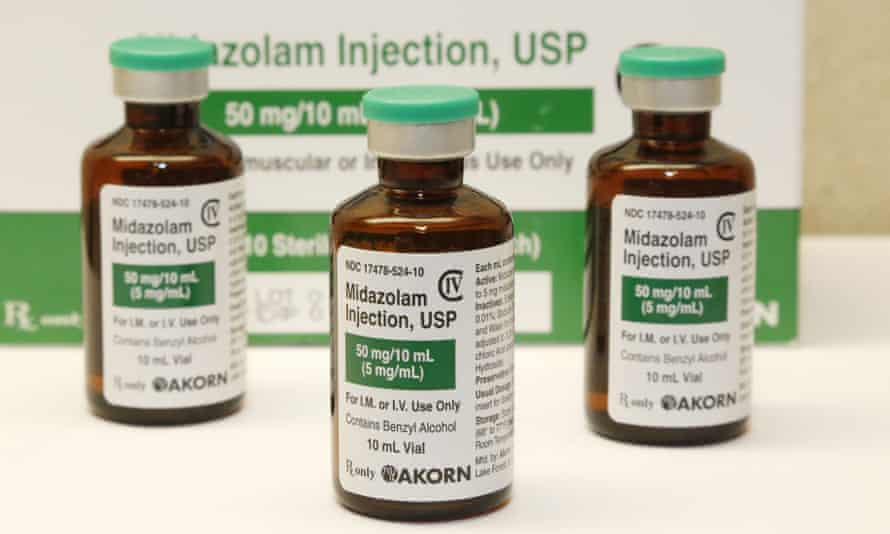

Midazolam, a short-acting drug also used to combat seizures, has well-known side effects including the slowing – or even stopping – of breath.

It is used in tandem with physical restraint around Australia, but guidelines – and even definitions – vary state to state.

“When you combine physical restraint, increased oxygen demand and possible impairment of lung movement with drugs that reduce conscious level and respiratory drive, the effects are going to be more significant,” said Dr Hugh Grantham, the former head of the South Australian Ambulance Service.

Dr Minh Le Cong of the Royal Flying Doctors Service, said in his experience administering midazolam to patients would often be either “ineffective, or too effective”.

“You’d either just keep giving more and more doses, or then when it did work it would work too well in that the person would be in a medically induced coma,” he said.

According to a report by the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network (the state body providing healthcare for those in the justice system), Dungay was physically restrained by a team of specialised critical incident officers after he refused orders to stop eating biscuits and became aggressive.

He was moved to another cell and while the Immediate Action Team restrained him again a nurse injected Dungay with 10mg of midazolam. Moments later Dungay stopped breathing. Staff attempted resuscitation for 40 minutes while ambulance officers were called but he was pronounced dead at 3.42pm.

The Justice Health report noted he had been administered midazolam after becoming hostile on at least one other occasion.

Police said Dungay’s death was not suspicious, but this is not accepted by his family.

Dungay’s mother, Leetona Dungay, told Guardian Australia: “He shouldn’t even have been injected. At the time he wasn’t even monitored or anything to even inject that.”

Leetona Dungay has rallied on each anniversary of her son’s death. In December she told the gathered crowd she had watched a video of Dungay “dying right here in this prison”.

“No mother should have to watch her son die right there in front of her on a TV screen.”

An autopsy report did not make conclusive findings or determine a cause of Dungay’s death, which is the subject of an upcoming coronial inquest. The report did recommend further expert assessment of whether the midazolam injection at all contributed.

Four months before Dungay died, NSW changed its guidelines to reflect the findings of two studies conducted at the Calvary Mater hospital in Newcastle. These studies showed midazolam has a higher chance of presenting adverse side effects – including a reduction in oxygen levels, airway obstruction and hypotension – than the alternative droperidol.

The new guidelines moved midazolam to a last-line sedative agent and designated droperidol as the primary agent.

Le Cong said at some point in the last three decades the use of midazolam shifted from being primarily a pre-anaesthetic to a drug for dealing with agitated patients in emergency departments, and questioned its continued use.

“The only reason we use midazolam as a chemical restraint, is because we use midazolam as a chemical restraint,” he said.

Dr David Taylor, who has studied the use of midazolam in Victorian emergency departments, said hospitals have strict procedures and guidelines in place.

“It’s always mandated that you have someone giving the drugs to sedate the patient, and another person who is there observing the patient,” said Taylor.

Managing the risks of midazolam outside the controlled environment of the emergency room is more difficult, he said, and if staff don’t have the training and equipment to pick up the side effects or manage them appropriately, “then it could be a potentially dangerous situation”.

According to the Justice Health report on Dungay’s death, nurses moved away to the door for their own safety after injecting him, in keeping with what they believed was department policy.

The report said Justice Health nurses had “minimal experience with primary health emergencies” at the time.

Current policy, updated in June 2016, simultaneously dictates medical staff must remove themselves from the vicinity of the restraint while also ensuring continued monitoring of the patient’s health.

Other deaths in custody have also been associated with the combination of chemical and physical restraint.

Coolwell died in October 2015 after being restrained in the prone position and administered midazolam. His case is scheduled to go before the Queensland coroner’s court this week.

Lyji Vaggs, who had schizophrenia, died in April 2010 in a north Queensland hospital two days after being restrained in the prone position and administered midazolam. The coroner ruled that the drug played a role in his death and his family was later awarded $100,000 in damages.

In 2008 William Wallace died in custody in circumstances that also involved midazolam and physical restraint. The coroner concluded that while the connection between the midazolam injection and Wallace’s collapse was a “standout feature” of the circumstances, it was “simply impossible to say that on a balance of probabilities it had made any contribution at all”.

“It remains a theoretical possibility, but one which cannot be elevated to a degree of probability,” he said.

After Wallace’s death in 2008, South Australia recommended changes to its guidelines for paramedics to prevent the combined use of the drug and physical restraint.

The coroner heard these new guidelines dictated paramedics no longer give midazolam to patients who are prone, handcuffed behind their backs or being restrained by a person’s body weight.

Bernadette McSherry, professor of law at the University of Melbourne, said there is inconsistency between state laws and guidelines.

“Different areas are regulated in different ways. It’s very piecemeal, and chemical restraint is particularly concerning in that in it’s not really regulated as much as physical and mechanical restraint. There is obviously a gap there.

“Because there may be little oversight in what happens in closed facilities like prisons and locked wards, people don’t know that it occurs. I think it’s only when you have a death, unfortunately, that this gets highlighted, as occurred recently in NSW.”

McSherry said once national reporting requirements on the use of restraint in mental health facilities was implemented in the UK, rates began to fall.

“There’s a real need to see national guidelines, reporting and monitoring of all forms of restraint across all closed facilities,” she said.

The Dungays’ lawyer, George Newhouse, declined to comment ahead of the inquest, but at a protest in December said their grief had been exacerbated by delays in seeing “justice”.

“All they want is justice, accountability and they want reforms to be implemented to ensure that no family has to go through the pain that they have experienced ever again,” he said.

“The family of David Dungay Jr had to watch their loved one die begging those officers restraining him, dozens of times, to simply allow him to breathe. Those pleas went unheeded and David died in excruciating circumstances.”

Justice Health said it was unable to answer questions on Dungay’s death as the case was currently the subject of a coronial investigation.

“Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network is deeply saddened by Mr Dungay’s death and extends its condolences to his family,” a spokeswoman said.

The Dungay inquiry is scheduled to begin in July.

Source : https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/mar/06/doctors-issue-warning-over-tranquilliser-linked-to-deaths-in-custody